Fat Scoring

Fat scoring (also known as Body Condition Scoring) is a way to determine whether your horse is a healthy weight. There are three key areas to consider: neck, middle and hindquarters. Fat will feel spongey whereas muscle is firmer, you’ll need to get hands-on to help you determine between them. The only exception to this is dangerous crest fat, which can feel hard and be difficult to move from side to side.

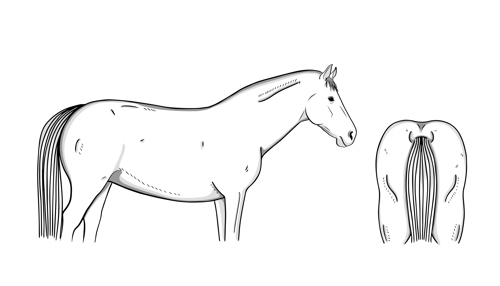

Score each of the key areas individually from 0–5 using the images and descriptions below. A healthy fat covering is a score of 2.5–3 out of 5, unless your vet advises otherwise. It can be normal for horses in hard work (for example racehorses) to look as if they're underweight but they’re physically fit and healthy with well-developed muscles.

Using a weigh tape, alongside fat scoring every two weeks, will help you to monitor your horse’s weight. Weigh tapes may not be 100% accurate but are a good tool to help monitor if your horse is maintaining, losing or gaining weight. If you have access to a weighbridge this will provide an accurate weight for your horse. We offer owners and carers the opportunity to weigh their horses by bringing a weighbridge to your yard. Your vet practice or local feed company might also offer this service.

You’ll need to use a different fat scoring system to assess the weight of your donkey. You can find the Donkey Body Condition Score Chart on the Donkey Sanctuary’s website.

play-circle

play-circle

Introduction to Fat Scoring Horses

Horse fat scoring chart

The chart below will help you to work out your horse’s fat score.

0 – very unhealthy (emaciated)

chevron-down

chevron-up

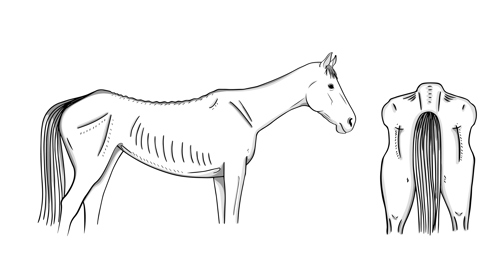

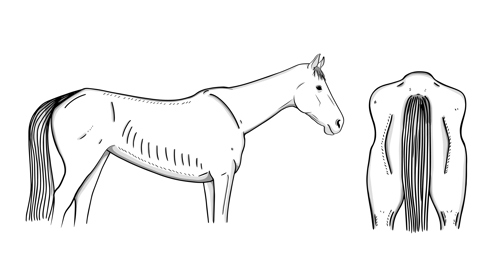

An emaciated horse will be extremely thin with little muscle and no fat covering. You’ll be able to see and feel each of the horse’s bones and the skin will look tight across the body. The horse will have a large gap between their hind legs.

1 – unhealthy (thin)

chevron-down

chevron-up

A thin horse will have slightly more fat covering their body and very little muscle. You’ll be able to see and feel each of the horse’s bones easily. The horse will have a large gap between their hind legs.

2 – moderate (lean)

chevron-down

chevron-up

Most fit racehorses or eventers will usually be this fat score.

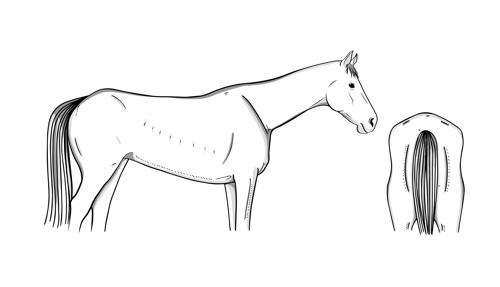

You’ll be able to see the shape of the horse’s muscles across their body with a very thin layer of fat. The ribs will be just visible and easily felt, along with the spine. There’ll be a slight gap between the hind legs.

3 – healthy (good)

chevron-down

chevron-up

A fat score of 2.5–3 is ideal for most horses, unless your vet advises otherwise.

The shape of the muscles will be less clear on a healthy horse, and there’ll be a thin layer of fat covering the body. The horse will have no crest, and you’ll be able to feel the nuchal ligament along the length of the neck. Ribs and spine can’t be seen but easily felt with light pressure. The hindquarters have a smooth curve between both point of hips, which can be felt along with the top of the pelvis.

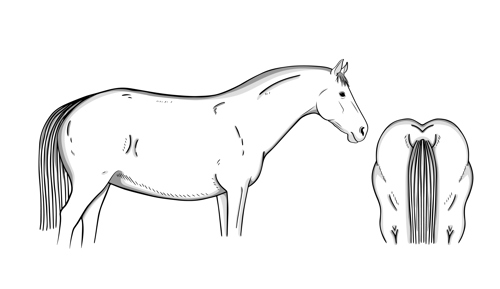

4 – unhealthy (fat)

chevron-down

chevron-up

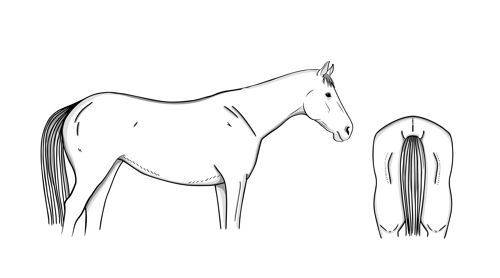

The shape of the horse’s muscles can no longer be seen, and spongey fat can be felt along the crest, behind the shoulder and across the hindquarters. You may be able to feel ribs but only by applying firm pressure. A gutter is forming along the spine and an ‘M’ shape on the hindquarters can start to be seen.

5 – very unhealthy (obese)

chevron-down

chevron-up

The horses’ neck is wide, and a large firm crest where hard fat has formed along the neck. Ribs can’t be seen or felt, and the horse appears to have a ‘flat’ back. You may notice large pockets of fat forming across the body. The point of hip and pelvis can no longer be felt, and a deep gutter has formed along the length of the spine with a definite ‘M’ shape being seen.

How to fat score your horse

Step one – neck and shoulders

chevron-down

chevron-up

Look at whether you can see the shape of the neck muscles. Feel along the crest and notice if there’s thickened, hard fat and if you can wobble it from side to side. You should be able to feel the horse’s nuchal ligament which runs along the length of the horse’s neck, located near the top of the mane, it should feel like a ball of elastic bands. Take care when feeling for the nuchal ligament with horses that are carrying excess fat on their neck as the area will feel inflamed when pressure is added. Muscle is below the nuchal ligament, any excess fat will sit above, so be careful not to confuse this as being topline. Stallions will naturally develop a crest on their neck due to increased hormones.

Run your hand down the neck onto the shoulder. Fat can accumulate in front of their shoulder blades, which can cause your hand to move smoothly over the neck onto the shoulder, instead of being stopped by the shoulder blade (which ideally should be clearly defined). You may also feel fat pads behind the shoulder blades too.

Step Two - Middle

chevron-down

chevron-up

Run your hand over the ribs; ideally you should be able to feel them easily with light pressure but not see them. If you have to press firmly or can’t feel them at all then your horse is carrying excess fat.

Placing your hand approximately a hand’s width away from the withers, follow the shape across the horse’s back. Ideally your hand should follow the arch over the spine and be able to feel the backbone. When you lift your hand up, away from the back, it should have a nice curve. Fat can build up on either side of the spine until it reaches a point of being higher than the spine and creating a gutter; this will often result in your hand lying flat across their back. If your horse’s spine is very visible and easy to feel, this indicates a lack of fat covering this area and your hand would have a more angular shape.

Step three – hindquarters

chevron-down

chevron-up

Run your hand over the horse’s hip bones, top of the pelvis and tail head — you should be able to see and feel them easily under a thin layer of fat. If you have to press firmly or can’t feel them at all then your horse is carrying excess fat. If the hip bones are prominently ‘sticking out’, the top of the pelvis is prominent and both are very easy to feel, the horse is underweight.

Stand a safe distance behind your horse to look at their hindquarters; ideally this should be slightly rounded – like the letter C. An ‘M’ shape and a gutter along the backbone would indicate too much fat. If the quarters drop away and become very angular, this indicates that the horse is underweight.

Why is excess weight gain an increasing problem?

Compared to Thoroughbreds, draught-types, cobs and native breeds are more likely to be overweight or obese. These horses have evolved to survive harsh, cold, wet winters and make the most of poor-quality grazing, with Shetland ponies being a prime example. The way that horses are managed now, means many have access to quality grazing all year round and are exposed to milder winters with additional rugging and stabling. As a result, horses don’t have to use as much energy to keep warm and with plenty of calories being consumed, their weight will begin to increase.

What's the danger?

Worryingly, in the UK up to 50% of horses are obese, with this figure creeping up to 70% in some native pony breeds1. Horses carrying too much fat can be at an increased risk of health issues such as Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS), laminitis and arthritis which can be detrimental to their welfare. Excessive weight gain more than doubles the risk of laminitis in horses and ponies2 — highlighting the importance of regularly monitoring your horse’s weight.

Horses with EMS and/or Cushing’s Disease can be trickier to fat score accurately. This is because horses with EMS tend to have abnormal fat distributed, for example, fat pads on their neck and hindquarters. Horses with Cushing’s Disease may also have abnormal fat distribution but could have muscle wastage and a pot-bellied appearance with their ribs visible. Speak to your vet for advice.

References

chevron-down

chevron-up

1) Rendle, D., et al (2018) Equine obesity: current perspectives UK-Vet Equine. 2(5).

2) Wylie, C.E., et al (2013) Risk factors for equine laminitis: a case-control study conducted in veterinary-registered horses and ponies in Great Britain between 2009 and 2011. The Veterinary Journal, 198(1), pp.57-69.