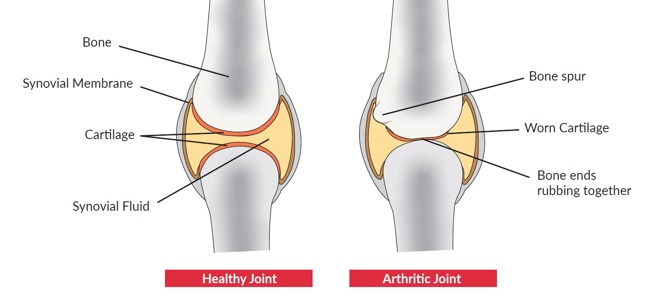

Horses can develop arthritis at any age; however, it’s more commonly seen in elderly horses due to years of wear and tear. In healthy joints a firm rubbery material called cartilage covers the ends of each bone providing a cushioning and allows for a smooth, gliding surface for movement. In arthritic joints the cartilage can wear away or become damaged leading to joint damage and pain.

Types of arthritis

Osteoarthritis

chevron-down

chevron-up

The most common long-term condition of the joints and is a result of continuous wear and tear, leading to cartilage damage. Over time as the condition worsens, bone may also deteriorate and develop growths known as ‘spurs’. This form of arthritis is most often seen in elderly horses.

Signs:

- Pain, stiffness and swelling around a joint

- Lameness

- A change in warm up duration – often takes longer for the horse to feel loose and ready to work

- Decreased performance

- A change in joint shape due to bone growths

Neck arthritis

chevron-down

chevron-up

Often associated with ageing horses, osteoarthritis can also develop between the vertebrae along the horse’s neck and is often associated with nerve damage1. This can influence how the horse moves as they use different muscles to try and stabilise their neck.

Signs:

- Pain

- Muscle loss

- Difficulty grazing / eating from the ground

- Weight loss

- Difficulty pulling hay from a net

- Lameness

- Reduced performance

Infectious arthritis

chevron-down

chevron-up

This form of arthritis is caused by an infection of the joints. Infection may be the result of injury, injection into the joint, transfer through the bloodstream or surgery and causes roughening of the smooth joint surfaces.

Signs:

- Swelling and heat around the joint

- Pain and restricted movement

- Lameness

- Lethargy

- Increased temperature

Traumatic arthritis

chevron-down

chevron-up

Accidental injury to the joint can cause joint inflammation however, traumatic arthritis can also be caused by osteoarthritis. In some cases, the cartilage can wear away or become so damaged that bone begins to rub on bone, leading to further joint damage and pain.

Signs:

- Pain, stiffness and swelling around a joint

- Lameness

- Decreased performance

- A change in joint shape

- Tenderness of affected limb

Diagnosis

Early detection and accurate diagnosis are important to get the inflammation under control and help the horse to live a comfortable life. Your vet may want to assess your horse in walk and trot on a soft and hard surface both in a straight line and on the lunge.

Flexion tests may also be completed to help detect any specific joint pain. This is where the vet will flex the joint for 30-60 seconds and the horse is immediately trotted away.

In addition, nerve blocks can be used to support the diagnosis and allow your vet to localise your horse’s lameness. If following a nerve block in a specific joint your horse’s lameness improves, this gives a clearer indication of where the problem lies and allows for a more targeted management plan.

X-rays, ultrasounds and MRIs can also be used to provide a definite diagnosis. Your vet will likely want to make regular reassessments to ensure the management options are effective.

Vet performing hind limb flexion test

Management

If your horse is diagnosed with arthritis the goal should be to reduce inflammation, pain and further damage through appropriate management and veterinary support.

There are several ways you can help your horse:

Managing weight: horses carrying excess weight will have added unnecessary stress and strain to their joints. Monitoring your horse’s weight through fat scoring and using a weigh tape every two weeks will allow you to react to any changes.

Exercise: depending on the location and severity of your horse’s arthritis, exercise (as advised by your vet) can be beneficial in reducing stiffness. The type of exercise and workload should be regularly assessed to make sure your horse is coping and comfortable with what you’re asking of them. Doing too much with your horse can lead to further joint damage and inflammation.

Discuss your horse’s exercise plan with your vet and an Accredited Professional Coach to make sure you’re tailoring the work to your horse’s capabilities. If your horse cannot be ridden, regular turnout or walks in-hand may be the best option to encourage gentle movement.

Turnout: optimise turnout to encourage gentle movement around the pasture. To avoid arthritic horses being chased around, turn them out with quiet companions. Consider appropriate footing as steep hillsides, rocky or uneven terrains are unlikely to be suitable; aim to use a pasture that’s as flat and even as possible.

Stabling: long periods of time spent being stabled should be avoided. Arthritic horses can become increasingly stiff and sore when stood in a stable for prolonged periods of time. If turn out is limited, consider whether your horse could be turned out in a safe arena and where possible include in-hand or ridden exercise in your horse’s routine. Some yards have access to barns or larger stables which can be ideal to provide more space where turnout is limited. In some cases of arthritis, box or field rest may initially be recommended to aid recovery, your vet will advise on what is best for your horse.

Transporting: caution should be taken when transporting an arthritic horse. Travelling can be strenuous for horses and those suffering with arthritis may become increasingly stiff and sore. If you have concerns, your vet will be best to advise.

Quality of life: regularly assess your horse’s quality of life considering their mental and physical wellbeing. Documenting this closely will help to identify any positive or negative changes. In circumstances where your management may be restricted, or the condition worsens, this will be something you need to consider.

Veterinary support

As well as changes to your own management, there are options your vet may suggest:

Anti-inflammatory/pain relief: the most common drug used to help manage horses’ pain and reduce inflammation is phenylbutazone (bute). If used appropriately, and under your vet’s guidance, this can be beneficial in successfully managing arthritis. However, continuous use of bute over a long period has been associated with signs of stomach issues including gastric ulcers as well as liver and kidney damage2,3. Your vet will be best to advise on the correct dosage of bute for your horse’s pain management.

Joint supplements: these may be beneficial for supporting horses with arthritis. Always speak to your vet for their recommendations.

Medicated injections: in some cases, directly injecting the joint with medication can also be an option.

Steroids are often used, and work to reduce inflammation in the joint. Some horses may require multiple injections to maintain this management technique4. Your vet will be best to advise on the injection intervals for your horse. Things to be aware of include a risk of infection at the injection site and if your horse has underlying health conditions predisposing them to laminitis, as steroids can increase their risk of laminitis developing5. Medicated injections should only be used in specific cases of arthritis, as recommended by your vet.

Hyaluronic acid can be injected into the joint which protects the joint from damage and helps reduce inflammation. Your vet will advise if this is suitable for your horse.

Antibiotics: if your horse is suffering with infectious arthritis your vet will be best to advise on the appropriate course of antibiotics to treat the infected area.

Arthrodesis is a last resort to relieve discomfort if anti-inflammatory medication doesn’t work. In low motion joints, fusing the bones together relieves the pain caused by arthritic changes, which can be done through surgery or injecting the area. Some horses may become sound enough for low level work, but this should be judged on the individual horse and with close communication with your vet6.

References

1) Ross, M. W & Dyson, S, J. (2011) Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in the Horse. Second Edition. Saunders of Elsevier. P. 613.

2) Ricord, M. et al (2020) Impact of concurrent treatment with omeprazole on phenylbutazone-induced equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS). Equine Veterinary Journal. 53(2). P. 356-363.

3) Davis, J.L. (2015) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated right dorsal colitis in the horse. Equine Veterinary Education. 29(2). P. 104-113.

4) McIlwraith, C.W. (2010) The use of intra-articular corticosteroids in the horse: What is known on a scientific basis? Equine Veterinary Journal. 42(6). P. 563-571.

5) Mcgowan, C, et al. (2016) No Evidence That Therapeutic Systemic Corticosteroid Administration is Associated With Laminitis in Adult Horses Without Underlying Endocrine or Severe Systemic Disease. Veterinary evidence. 1(1).

6) Zubrod, C. & Schneider, R. (2005) Arthrodesis Techniques in Horses. Veterinary Clinics: Equine Practice. 21(3). P. 691-711.

Get in touch – we’re here to help

The Horse Care and Welfare Team are here to help and can offer you further advice with any questions you may have. Contact us on 02476 840517* or email welfare@bhs.org.uk – you can also get in touch with us via our social media channels.

Opening times are 8:35am - 5pm from Monday – Thursday and 8:35am - 3pm on Friday.

*Calls may be recorded for monitoring purposes.